Childcare workers who work for Courtney and others are pioneers in what, some observers say, is a national push toward prioritizing our children, the parents who require childcare subsidies, and childcare employees who are there when the parents are not.

Childcare worker Amril Samatar, who is active with KCOU. Photo courtesy of KCOU.

“Not only are they [childcare workers] changing things for the better for themselves, their families, and their communities. They are also shining a light on the unjust structure of our economy that pays unlivable wages to those who care for our children and loved ones.”

Jen Racho

Program Officer, Northwest Area Foundation

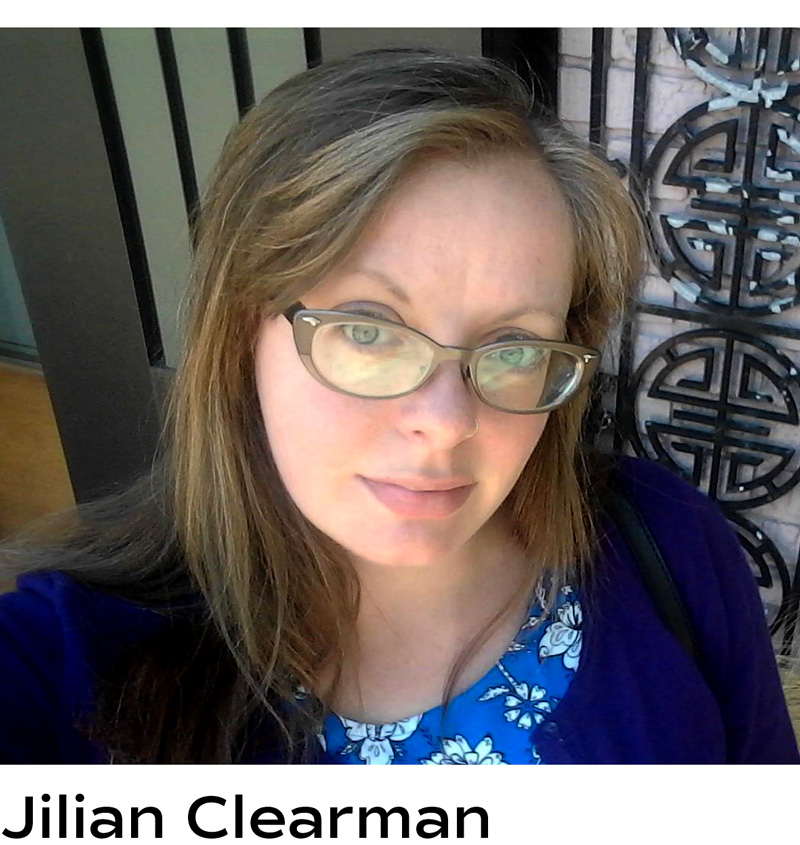

Those triumphs were outcomes of Confluence-backed efforts of KCOU. As that coalition continues its conversations and collaborations with labor leaders, says Jilian Clearman, Confluence’s fundraising director, it’s deciding what the coalition will look like going forward.

KCOU’s lobbying helped persuade the Minnesota Legislature this year to approve the historic surge in childcare funding that will cover new hiring of childcare workers at higher salaries. It also will maintain income-based childcare subsidies for needy families.

Lydia Boerboom, KCOU, (far left) sitting with participants connecting during a post-legislative session event co-hosted by Confluence and the McKnight Foundation. Photo courtesy of the McKnight Foundation.

“People stick with this because the work is deeply emotional and fulfilling. They are learning that they deserve so much better. And that’s what this organizing is all about.”

Lydia Boerboom

Lead Organizer, KCOU

Read the first blog in this series:

Photo top: Lydia Boerboom, KCOU lead organizer (kneeling front) with KCOU supporters. Photo courtesy of KCOU.