My own diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) journey is making me take a second look at a number of things in my life, including how I show up as a white male leader in philanthropy.

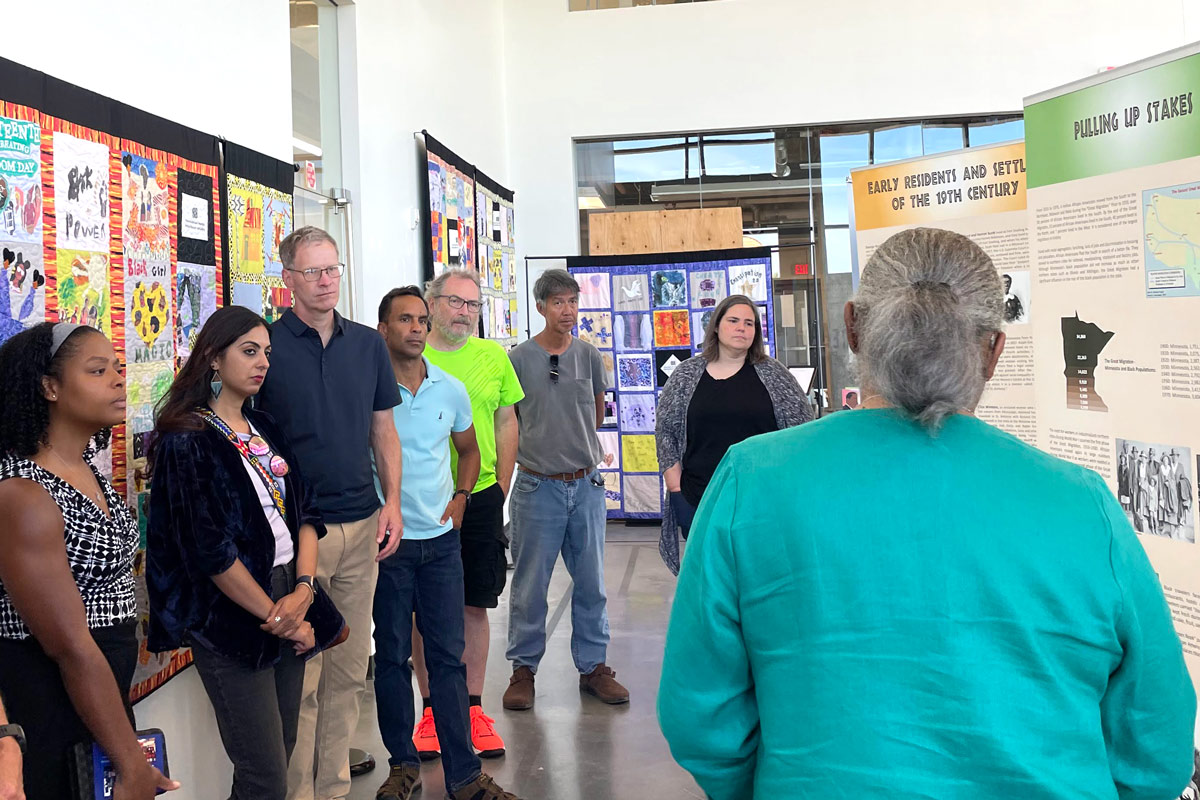

Recently, a nonprofit board I serve on held a board retreat. It was nothing fancy, just two half days in the nonprofit’s conference room. But the retreat gave us time to have a long conversation about the mission-critical importance of DEI.

The retreat began with a warmup question for staff and board alike: “Share a reflection on a time that your identity—who you are—changed or informed a conversation in a way that was visible to you.”

That’s quite a question, and our answers varied a lot based on our identities. Several people shared stories that lifted up lived experience with racism, homophobia, and sexism. But the incident I decided to share was different. It’s a story that, back when it occurred, I told for laughs. As a frequent business traveler, I viewed it as a funny example of the bizarre things that can happen on the road.

But in the context of this meeting about DEI, I saw that it’s a revealing story about the skin I’m in. And it could have been a tragic story if my skin were different.

A seemingly harmless impromptu decision.

About 10 years ago, I traveled to visit some of the Northwest Area Foundation’s grantee partners in northern North Dakota. I flew from the Twin Cities to Minot, rented a car, then headed northeast to the small town of Dunseith.

After spending an hour or two in conversations there, I got back in the car and set off toward Belcourt on the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indian Reservation.

I was running a little early for my dinner meeting in Belcourt. So when I approached the International Peace Garden on the Canadian border, not far from the reservation, I thought I’d check it out. I had heard about it, but wondered what an “international peace garden” would be like.

“I made a slow U-turn around the gatehouse to head back out to the main road. That’s when my afternoon went sideways.”

As I drove up to the gatehouse, though, I saw that there was an entrance fee. Not a huge one, but enough that it seemed wasteful to pay when I’d only have a few minutes to spend there. So I made a slow U-turn around the gatehouse to head back out to the main road. That’s when my afternoon went sideways.

A disturbance to the peace.

I stopped the car and rolled down the window to explain to the uniformed man inside the gatehouse that I’d decided I didn’t have enough time to visit. But instead of waving me through, he started giving me very precise instructions, while two other men in uniforms approached my rental car.

His orders went something like this:

- Sir, put your hands on the wheel at ten o’clock and two o’clock.

- Now, use your left hand to reach across the steering column and turn off the engine.

- Remove the keys from the ignition with your left hand and drop them on the floor of the car.

- Put your left hand back on the wheel.

I obeyed each command in turn. Then in a louder voice he said to his officers, “OK—pull him out and cuff him.”

The two other men grabbed me from the car, pinned my arms behind my back, clicked cold metal handcuffs tightly around my wrists, and hustled me into the gatehouse.

“OK—pull him out and cuff him.”

This was pretty amusing. Or was it?

As I said, I used to tell this story for laughs—the notion of me, a mild-mannered, bespectacled foundation CEO, being dragged at random from a rental car and cuffed.

I often talked about how one of the officers stood over me inside the gatehouse, firearm holstered at his hip, and chatted me up as if we were waiting in line at a Dairy Queen. We both have two sons, and we both like hockey. Gee, what a coincidence! Small world.

The story gets tenser when the senior officer starts methodically grilling me about who I am and why I’m here. I tell him the truth, but it comes out sounding like a ridiculous lie.

Turns out it sounds pretty fishy to explain that your organization gives out money to people fighting poverty. It sounds like pure nonsense, or a criminal conspiracy. It sounds like the cock-and-bull story of somebody who’s about to spend the night in a holding cell.

“Turns out it sounds pretty fishy to explain that your organization gives out money to people fighting poverty.”

A mere inconvenience?

I’ve also managed to wring laughs out of the fact that they searched the car, unpacked my suitcase, held onto me for another 30 minutes or so—then thanked me and let me go. As we said our goodbyes, one of them handed me a customer service questionnaire asking questions along the lines of:

How did we do today?

How would you rate today’s detention and interrogation experience?

Would you recommend these officers to a friend in need of detention?

Really? I never returned the survey, and I’ve never gone back to visit the International Peace Garden.

“Only now do I understand how much this story has to do with my identity. . . . I’m a white, straight, well-educated, middle-aged man, and a US citizen with a job and a valid driver’s license. I have never, not for one moment, felt at risk in the presence of police . . . ”

“We get hassled all the time like that, you know.”

I’m not telling that tale for laughs anymore. I understand how much this story has to do with my identity—with who I am and how I move through the world.

I’m a white, straight, well-educated, middle-aged man, and a US citizen with a job and a valid driver’s license. I have never, not for one moment, felt at risk in the presence of police because of the color of my skin, my immigration status, or any other aspect of my appearance or identity. And for the entire duration of this incident near the Canadian border, I had a clear sense of what to do:

Stay calm. Breathe. Try to relax. Answer their questions. Be courteous, not confrontational. You’ve done nothing wrong. This is some kind of mistake. They’ll figure that out, and then they’ll let you go.

And that’s exactly what happened.

When I got to Belcourt, the deep, discolored grooves left on my wrists by the handcuffs turned out to be a great conversation starter. Our grantee partners from the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa agreed with me that I’d had an absurd experience at the Peace Garden. One of them said, “We get hassled all the time like that, you know.” And we laughed some more.

But his comment kept echoing in my mind that night. Hassled all the time like that? Hassled why? What was the meaning behind what he was telling me?

What if I weren’t a white male foundation CEO?

My experience with those officers on the border could’ve taken a tragic turn if I weren’t white. Not until the other day, responding to that prompt—“a time that your identity—who you are—changed or informed a conversation in a way that was visible to you”—did I see just how many ways my whiteness played to my advantage that day.

“Because my identity, who I am, carries with it a lifetime of learned trust that the system will not attack me. I was confident that the uniformed men would not decide to assault me. . . . Would the outcome of my detention have been any different if I were a person of color? An immigrant? A tribal member from Turtle Mountain instead of an executive from St. Paul?”

I was erroneously detained, but then released unharmed in less than an hour. Why? I was able to stay calm and cooperative while being manhandled and intimidated for no reason by armed men. Why?

Because my identity, who I am, carries with it a lifetime of learned trust that the system will not attack me. I was confident that the uniformed men would not decide to assault me, that I would not end up injured or dead within a stone’s throw of the International Peace Garden.

And sure enough, when their computers indicated to them that, whatever they were searching for, I wasn’t it, they felt comfortable letting me drive away.

Would the outcome of my detention have been any different if I were a person of color? An immigrant? A tribal member from Turtle Mountain instead of an executive from St. Paul? I don’t know.

But I do understand now that it would have been entirely rational to fear for my safety under those different conditions. That is our nation’s history, and that is the current situation in our country. Unless we drive fundamental changes, it will be the future as well—a future that is a danger to individual lives but also a grave threat to the fabric of our democracy.

Facing up to a racist reality.

An incident that I once considered a funny travel yarn is really a different kind of story. And I think it can be a way for me to own up to and talk about the white privilege that I’m enmeshed in every day: inherent advantages possessed by a white person on the basis of my race in a society characterized by racial inequality and injustice.

“So an incident that I once considered a funny travel yarn has revealed itself to me as a different kind of story. . . . [White privilege] in the United States is hard for people like me to talk about. We avoid it for a whole host of reasons, including denial, guilt, and anger at being implicated in a racist reality.”

This fact of life in the United States is hard for people like me to talk about. We avoid it for a whole host of reasons, including denial, guilt, and anger at being implicated in a racist reality.

We also shy away from it, I think, because of a deeply ingrained commitment to the idea that, since each individual human being is unique and precious, we must not be reduced to categories or labels. That perspective often leads us to chafe at being identified as white or having attributes ascribed to us accordingly—attributes like my relative safety in that gatehouse.

Speaking up and speaking out.

But until we name these dynamics and own them, we cannot transform them. As writer and social activist James Baldwin said, “Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed without being faced.”

As a white leader in philanthropy who is committed to advancing DEI, I am determined to get better and more consistent at learning from my experiences, speaking up and speaking out. That includes telling my old Peace Garden story in a new way, alert to the meaning of the skin I’m in.

Author

Kevin Walker

President and CEO, Northwest Area Foundation

PRESIDENT’S BLOG SERIES: NO. 2

From the laptop of Kevin Walker, our president and CEO

This is the second in a series of quarterly entries that highlight issues sparking ideas and insight for Kevin and the Foundation. Read his other blog entries:

Tags: Diversity, Equity, Kevin Walker