The prevailing belief that funders and mainstream experts know best is a topic we discussed in our cohort on racial capitalism. Implicit in this belief is often an unacknowledged distrust of community leaders of color.

We made changes in our grantmaking approach and practices because of what we learned. Letting go of control is an ongoing journey for us, but grantees are cheering us on.

“You’re on quite a journey,” a grantee recently said about one of our new values: Grantees Come First. “Continue to let go and let community lead you. I have been told many times I need a coach. I think philanthropy needs a coach, and that coach is community.”

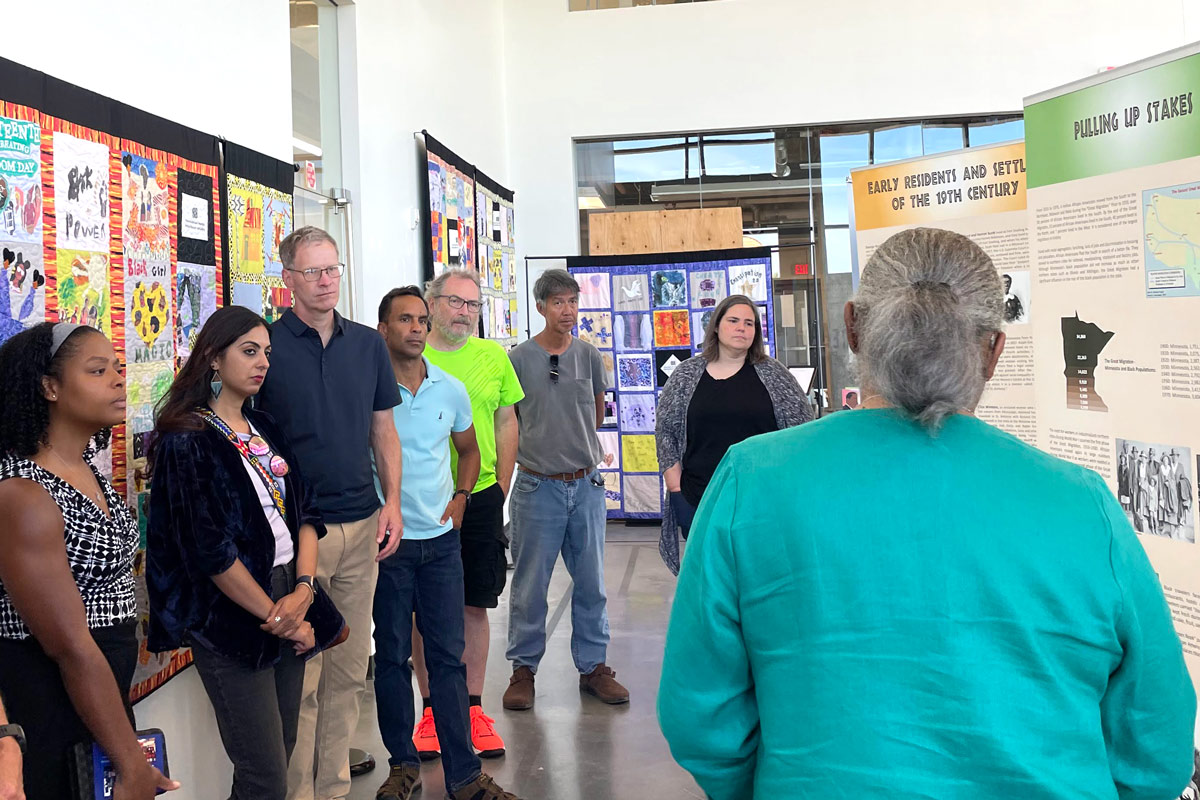

There’s a need for acknowledgement of racism and for healing and repair.

It is painful to acknowledge and reckon with the history of philanthropy, and that, as program officers, we may be unintentionally furthering racial capitalism. But we know that acknowledging and taking responsibility of past harm is the first step in healing.

And acknowledgement isn’t enough. We’ll continue to act. The Foundation has committed to advancing justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion. Foundation staff has spent time on intercultural development and learning about ways to dismantle white supremacy. And we’ve refreshed our organization’s values and updated our funding approach to center justice.

The new funding approach provides more general operating grants that give grantee organizations more control and flexibility in how to use the funds. It’s they who make decisions about spending, instead of the Foundation’s board or staff. It’s a small, but important, step toward balancing the power dynamics between foundations and nonprofits.

Our refreshed grantmaking approach also includes elements of self-determination and power, healing, and systems change. Grantee organizations have told us that these are critical conditions for advancing justice.

As program officers, we will continue to listen to and learn from people on the ground to understand the context of their lives and work. We will do that with humility, heart, and transparency. We’ll try to make sure resources are as flexible as possible and support grantees’ vision for disruptive change.